by Alita Byrd

This article was originally published by Spectrum Magazine in August 2020.

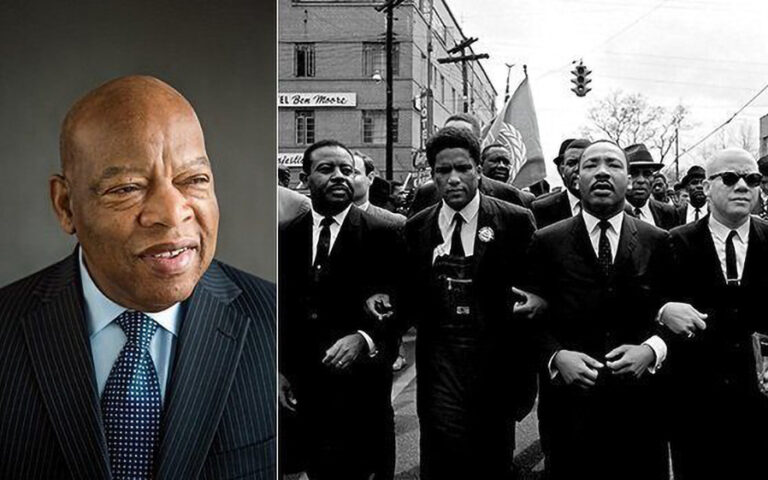

Rockefeller Ludwig Twyman — musician, public relations professional, community organizer, and campaigner — wants your signature on his petition to secure a Nobel Peace Prize for his friend, Congressman John Lewis, who died last month. He also asks for your prayers as he holds a vigil this week in front of the U.S. Capitol, urging members of congress to come back and extend benefits to people suffering as a result of the pandemic.

Question: You are spearheading a campaign to get Congressman John Lewis, who died on July 17, 2020, a Nobel Peace Prize. How is it going?

Answer: When he got sick [John Lewis announced a diagnosis of stage 4 pancreatic cancer in December 2019], God impressed me to start this campaign. He is so worthy. It was so sad that he passed.

The campaign [for the Nobel Peace Prize] is going slow. But we are trying to get this into more people’s hands. We are going a non-traditional route with this campaign, with a Change.org petition for signatures supporting it. We are hoping that we can get 100,000 signatures.

We need to put people out in malls to canvass and get signatures across the country. Like in Alabama, where he is from. Also, at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, which is Lewis’ school. I am hoping to go there and have a canvassing campaign and get people to sign. Then we are hoping to send all that to the Nobel Prize committee. And pray.

One of the criteria for a Nobel prize is that someone who has won has to nominate you. We are hoping that Barack Obama or Al Gore or President Jimmy Carter (Lewis was very close to Carter) might do the honors and nominate him. But that is something for down the road. Maybe we can have a prayer vigil down in Atlanta in front of President Carter’s center. The deadline [for the 2021 prize] is February 2021.

Maybe Obama will do the nomination. Obama said Lewis was one of the key reasons he got into office. He told him that when he was accepting the presidency on Inauguration Day.

I don’t think there will be any problem nominating him. But there is always a lot of competition for this prize.

Tell us about your background with John Lewis. How did you first meet him?

John Lewis and his wife Lillian did so much for me. They really helped me make my career.

A friend of my sister’s knew that Atlanta University was looking for people to work at the library there. Lillian Lewis was Head of Special Collections. I went there and interviewed, and she liked me. I think one thing that helped me get that job was that Lillian was really into the arts, and I was a music major.

John and Lillian Lewis were the reason I was able to go to La Sierra University. I would come home to Atlanta for the summer, and I always had a really good-paying summer job. That job helped me pay the next year’s tuition at university.

Another thing they did that was so wonderful was that the Lewises had me performing at all these big-time functions in Atlanta. I made connections with all these powerful people and that really helped me when I started my public relations firm.

God showered his blessings on me. It really was a blessing from God — there is no other way to explain it.

When John Lewis won the congressional seat [in 1986], our relationship continued. They gave me tickets to some of the biggest events here in D.C., like the Black caucus dinner. They treated me like a son, really.

Lillian Lewis was an artistic woman from California — she came from a very cultured background. When she was dying [in 2012], I went down there to Atlanta several times and played concerts on her piano. She had a fabulous piano, like a Kennedy Center piano — a grand in their living room. I would play her favorite hymns and classical music.

It really was something. To see them start out, and then go to congress for all those years. And they never forgot me either.

I am hoping to really do something to help the foundation that was just started in their honor: the John and Lillian Miles Lewis Foundation.

Another of your recent projects was writing, with composer and musician David Griffiths, a gospel song called Victory over the Coronavirus Song, which was choreographed and performed in front of the John Lewis mural in Atlanta. Why did you want to do this event?

I had never seen the mural before. [Created by artist Sean Schwab, the 65-foot mural was dedicated in 2012.] When I got there, I just cried. It was overwhelming. I realized I won’t see him again until heaven. It is such an impressive mural. It really is. It is an area [Sweet Auburn district] not far from the Ebenezer Baptist Church, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s church.

We planned the event to bring attention to the fact that people across the U.S. are losing their benefits.

I made a speech about John Lewis, and how he would have deplored this situation. We prayed. Our song was performed. Three television stations came out to cover it.

The day we did the event was the day Congress left town without a plan to help all of these people who are unemployed. This is so tragic. We are setting the country up for a French Revolution, where the poor people rise up against the rich people and the chaos takes over.

The choreographer for our song, Terrie Ajile Axam, is world-renowned, and has choreographed for some very famous people. We connected and she liked the song and said she would choreograph it for me.

It was a beautiful event. And as always, we tried to keep prayer as a focus.

John was a prayer warrior. Prayer was what sustained him throughout the civil rights struggle of the 1960s.

This event was significant because when John was alive, he really was into trying to find a solution to help people who were impacted by this coronavirus. If he had been alive, he would have really stood up about the non-renewal of those pandemic benefits to people. He knew this would severely impact minorities — not only in his Atlanta area but all across the nation. I think he would have really been riled up and tried to get on that Senate floor to tell them: “Don’t leave town!”

Going back, why did you choose La Sierra University? Where did you go to academy?

I went to Pine Forge Academy in the 1960s. The racism we experienced as Pine Forge students was something awful. I remember all the racist stuff when we played basketball against other schools, like Takoma Academy.

And why La Sierra? The music department was so good at La Sierra. And I think I just wanted a different scene. I had never been to California. I majored in choral conducting.

Tell us about conducting.

I have directed several choirs in the past.

I have a unique concept about choirs. I believe they should bless the community.

I was blessed when I directed the Capitol Hill Chorale at Wintley Phipps’ church in Washington, D.C. [from 1990 to 2000]. We sang in a lot of places, including for gunshot and stab victims in D.C. General Hospital. That concert was covered by all the press. We performed concerts for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day at a D.C. prison.

I tell Adventist musicians that it is great to sing for Adventist audiences. But we also have a commission to do community outreach. We should also be singing at soup kitchens and homeless shelters and those kinds of places. It is an opportunity to witness.

The Capitol Hill Chorale was such a blessing to the community. We did so many things.

I brought Lillian Lewis to the Capitol Hill Church. She wanted to come one Sabbath and hear Wintley Phipps preach. They were good friends. He sang a beautiful rendition of Amazing Grace as John Lewis’ casket arrived at the U.S. Capitol.

And after college, what did you do?

After I graduated from La Sierra in 1971, I went to Indiana University on a Ford Foundation fellowship, where I was involved in a research project about Black music. We were putting together a music dictionary of Black composers.

Then I lucked out and got a job at a TV station here in D.C. I later worked at WHUR, Howard University’s radio station, where I did community relations. That was wonderful because I met so many political and music people. I also worked for Tom Joiner, the big radio DJ, and did his press whenever he came to D.C. We did a lot of great community projects, like a Father’s Day breakfast for homeless veterans and a Valentine’s Day thing for homeless women.

I have also always played for a lot of different churches on Sundays, too. I can do gospel, and I can also do classical!

God has opened up a lot of doors — I just follow where he tells me to go.

When did you start Rocky’s PR Miracle, the public relations firm you now run? What kind of clients do you have?

In 2008, it started as a side job, when my main job was doing PR for St. Paul’s Episcopal Center.

But as I got into it, it became a major thing.

I have been doing political things for some local races here. But a lot of my clients are churches. I have felt a great need to let people know about the positive things churches are doing. The churches are being attacked right now, and the young people don’t want to go to church. So, I find things that churches are doing in their communities, like feeding the homeless. I have helped to organize many musical fundraisers for people who have been impacted by disasters, like Haiti, as well as disasters right here in America.

A lot of churches are really doing some wonderful stuff, but nobody knows about it. We try to show what they are doing.

I believe you have some opinions on how the Adventist Church has handled social justice movements and the campaign for racial equality in the church. When Spectrum was writing about the Adventist response to the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, I talked to you about the Vigil for Racial Healing you organized there, and you referred to the Adventist Church as a racist denomination. Do you still feel that way?

I sort of do still feel that way. Adventists have always trailed behind other denominations in civil rights, it seems to me. They just have not had a very deep commitment to civil rights.

Ted Wilson’s comments after George Floyd died were only lukewarm. I was disappointed. Wilson sang in my choir at La Sierra.

Whereas Dan Jackson’s [recently retired president of the North American Division] comments were very forceful. I met him recently and I was impressed by his racial sensitivity.

We have got to get past this. Because the Lord is going to come, and there ain’t going to be no white heaven and no black heaven.

I see more churches worshiping together, both Black and white. But we still have to have regional conferences because the pastors say if they all came together, they wouldn’t get a fair shake.

We need a spiritual revival.

It’s the same thing for the fight for women in the church. That is just ridiculous. That has just been unreal. It just doesn’t make sense, at all. They are doing the same job as the men, but you don’t want to ordain them or give them the same pay? That is just crazy.

All the non-Adventist churches I know have addressed this issue and moved on. Even the Baptists have gone out of their way to bring women in. And some of those women in the Baptist church can preach!

What could the Adventist Church do better when it comes to racial justice? What would be your advice?

We need to have more sensitivity sessions between the races. I think that there should be quarterly meetings where we come together and discuss our differences. We should pray and fast about them.

What other projects are you working on?

This week we are organizing an eight-hour prayer vigil in front of the U.S. Capitol, trying to get members of congress to come back to work and deal with this pandemic. They are all at home while people are suffering. I am just appalled at the long lines at food banks. The people who used to donate to the food banks are now standing in the line. We think the country is on the verge of an economic collapse.

Our socially distant vigil includes leaders of different faith communities. We’re not gonna hold no hands.

I organized the Pray at the Pump campaign in 2008, when gas prices were going crazy. That movement really caught people’s attention. And God really did bless that.

Now we want to call the nation’s attention to the need for prayer right now. The Democrats and the Republicans cannot come together. We need God to touch their hearts and touch the heart of President Trump. We need a speedy resolution to this problem.

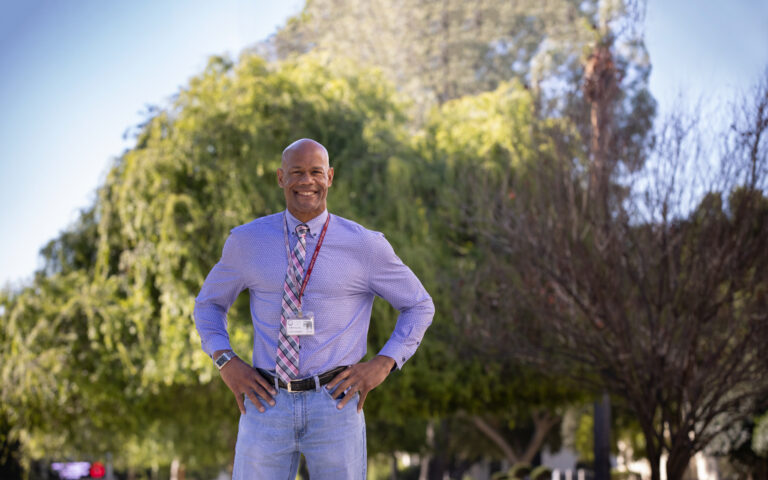

Rockefeller Ludwig Twyman is a professional musician and public relations professional and member of the Rockville Seventh-day Adventist Church in Maryland.

Alita Byrd is interviews editor for Spectrum.

Top photo: Rocky Twyman stands in front of the U.S. Capitol with Joan Mulholland, civil rights activist and friend of John Lewis. Photo courtesy of Rocky Twyman.