by Darla Martin Tucker

The collaborative work of scientists at La Sierra University and Walla Walla University has widened the scientific window into the potential effects of climate change and garnered international coverage of their findings.

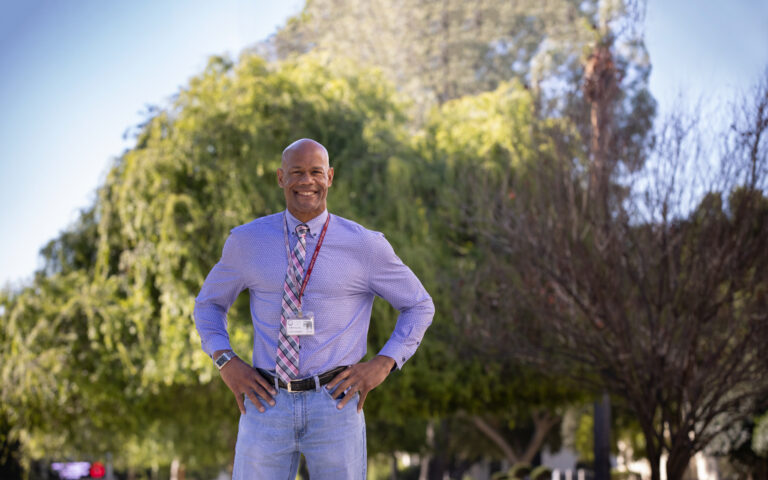

One of three Octopus rubescens in the lab at La Sierra.

At times using innovative equipment they engineered themselves, marine biologists Lloyd Trueblood, an associate biology professor at La Sierra University and Kirt Onthank, associate biology professor at Walla Walla University analyzed the East Pacific ruby octopus or Octopus rubescens in one and five-week studies at WWU’s collaborative Rosario Beach Marine Laboratory. It was the first analysis of octopus that compared short and long-term effects of sea water acidified through increased carbon dioxide levels. The journal Physiological and Biochemical Zoology from the University of Chicago Press published their research and issued a press release in January announcing findings that showed the octopuses had adapted to increased sea water acidity by returning to and maintaining normal metabolic rates, or energy usage levels after an initial reaction in which they used more energy following a first exposure.

Because the research was the first of its kind and sheds significant light on octopus’s potential adaptability over time to increased carbon dioxide which is linked to climate change, the journal’s press release garnered attention from numerous media outlets and websites around the world including in India, the Czech Republic, Israel, Jordan, and Canada as well as the United States. Coverage appeared in outlets such as Science Daily, Science Magazine, Yahoo!News, and Environmental News Network.

Results also showed that while their metabolic rate stabilized after one week, the octopuses had a decrease in their tolerance of hypoxia (decreased environmental oxygen), a potentially significant problem for animals who make their homes and hiding places in dens where stagnant water further decreases water-borne oxygen supplies.

Ocean acidification occurs when carbon dioxide or CO2, which results from fossil fuels spewing into the air, dissolves into the ocean causing a drop in pH levels and an increase in seawater acidity. The ocean absorbs about 30% of the CO2 released into the atmosphere, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, resulting in harm to marine life.

Trueblood and Onthank are building on results from their five-week study and exploring methods the octopus may be using to overcome the stress of acidic oceans, such as editing RNA, changing gill transport proteins, and modifying blood oxygen-carrying proteins. Students in both of their labs are assisting with the process.

The scientists initiated the five-week study of Octopus rubescens in the summer of 2014. They harvested the ruby octopuses from Washington’s Puget Sound where a naturally low pH level results in continuously high water acidity that is on par with predictions for ocean acidic levels this century. “We basically have a future test ground,” said Trueblood.

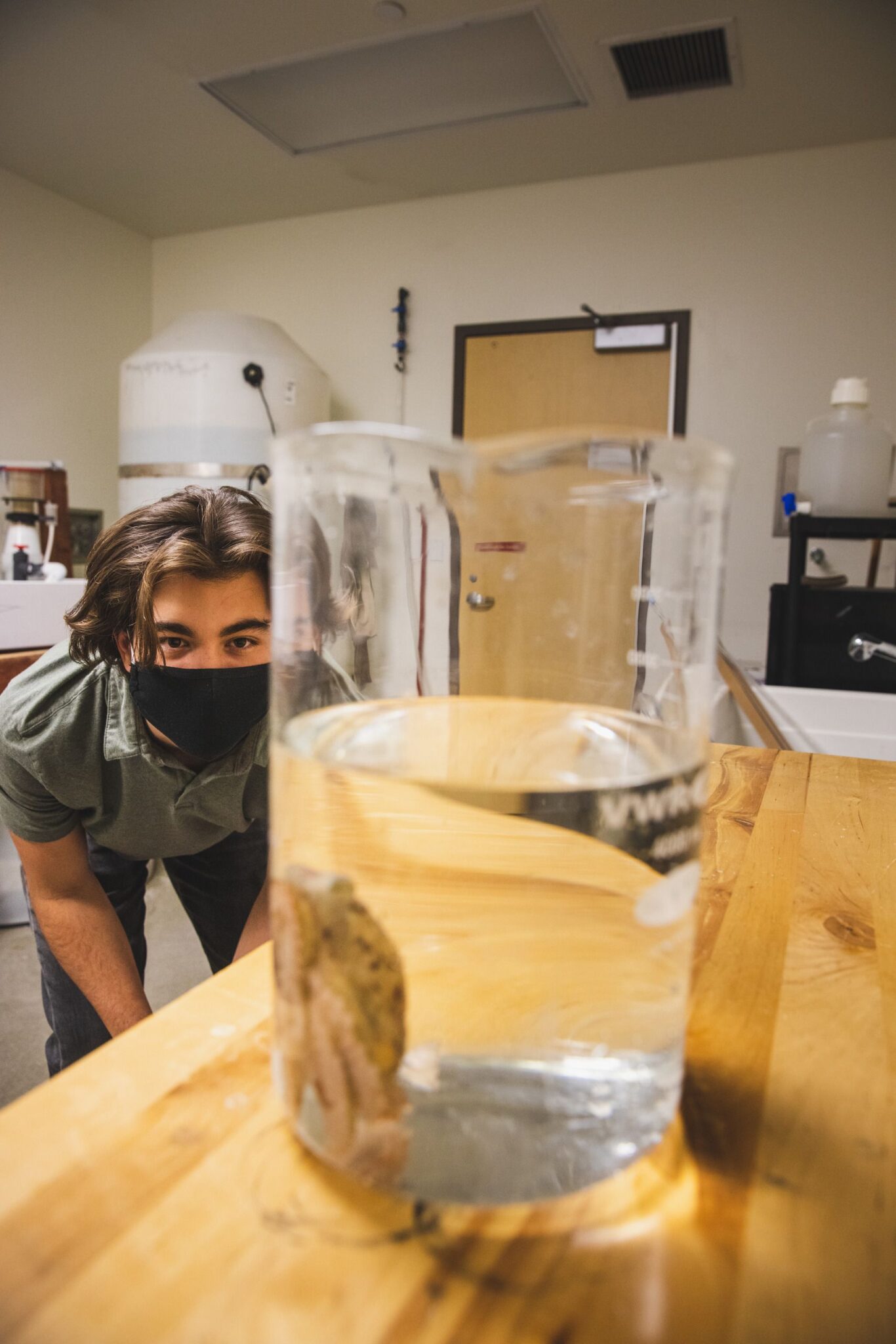

Student Danny Bazan checking on a ruby octopus

Onthank’s lab, which typically involves three graduate student researchers focused on octopus ocean acidification projects, has pursued several studies and made additional findings: a refined study in 2015 indicated that an increase in temperature combined with an increase in carbon dioxide resulted in a worsened metabolic rate for the octopus over five weeks; and a study of the octopus’ immune system after exposure to increased CO2 showed an elevation after three weeks of hemocytes, which are equivalent to human white blood cells. “Their immune system is being activated and turned up with long-term exposure,” Onthank said. “And now we’re looking at another thing octopuses and cephalopods do, this really crazy thing where they edit their RNA.”

Just ten minutes—that’s how long Trueblood’s student researchers have to extract a drop of blood using a tiny syringe to reach a vessel the size of angel hair pasta hidden inside of a small, slippery octopus. It is a difficult procedure, but critical along with work in Onthank’s lab to furthering the scientists’ groundbreaking research.

La Sierra University undergraduates Shannon Grewal and Danny Bazan are the latest students to make blood extraction attempts, currently working with three ruby octopus specimens that arrived from California’s Central Coast to Trueblood’s lab via FedEx on January 13. The students follow strict European-standard animal welfare protocol, which involves first anesthetizing the creatures and minimizing their time out of their specially formulated salt water tanks.

Over the years, only a handful of useable blood samples have been collected with only one successful sample collected by his two current students thus far, Trueblood said. “That’s half the challenge. Getting blood [from] intact animals is incredibly difficult.”

Learn more about student research in this article with senior Shannon Grewel

The blood-drawing process involves one student holding up the octopus to reveal an opening in its mantle and gently extending a gill with tweezers while another student strives to insert the needle into the gill. If this doesn’t work, the students aim for either a cephalic vein next to the systemic heart (octopuses have three hearts) deep inside the octopus’ mantle which houses its organs, or from an artery in one of the octopus’s arms. They study octopus anatomy beforehand and look at references as a guide while they attempt the extraction. They check for the correct needle gauge, or hole size in the needle’s end and make certain there is no pressure inside the needle. “It’s extremely difficult and frustrating, but on our first try, on [January] 25th, we were able to get blood,” Bazan said. About half a milliliter of blood was withdrawn.

Trying to draw blood for research is difficult but fun, said senior biomedical sciences major Grewal. “It’s a puzzle you have to solve. There aren’t a lot of people who extract blood from octopuses, so it’s kind of a surprise every time. It’s quite an adventure.”

For more on this story, please visit La Sierra News at www.lasierra.edu.