by Scott Steward

“He has shown you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?” –Micah 6:8 (NKJV)

“Some people were shocked by this pandemic, and even more shocked that racial minorities were disproportionately affected, but I wasn’t,” says Jeannie N. Shinozuka, Ph.D. “It’s been part of my research for the last two or three decades.”

There are few as specifically and uniquely qualified as Shinozuka to speak on the complex and interconnected issues of public health, race, and environmental history.

Shinozuka—who earned a BA in History and Political Science with a minor in gender studies from La Sierra University—teaches in International Studies at Soka University of America, a small private liberal arts college of about 450 students in Aliso Viejo, California. The classes are small, much like they were when she was an undergrad at La Sierra, and she is currently working to build an ethnic studies program for students of color with courses that reflect them.

“I was raised primarily as Japanese American Adventist,” Shinozuka explains. Born in 1976 to recent Japanese immigrants to Southern California, she grew up during the height of America’s bicentennial patriotism. “[Those identities] went hand-in-hand. It was all about community. I never saw them as separate. My immediate family never experienced the incarceration of Japanese Americans in the 1940s, but many in my community did. It has been hard to talk about,” she reflects. “These are the people who taught my Sabbath School classes and I interacted with every Sabbath.”

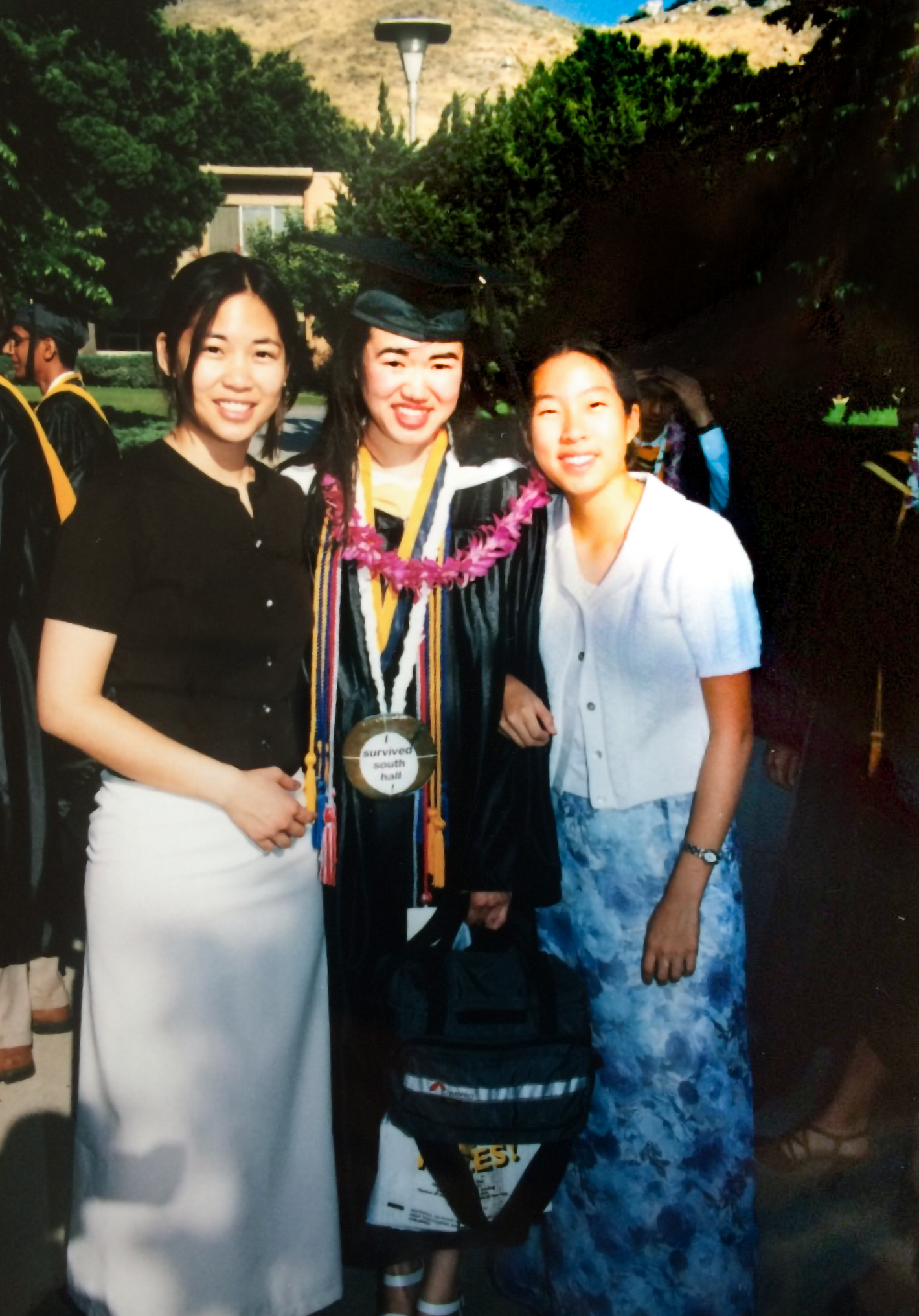

La Sierra graduation, 1999

As a La Sierra alumna, Shinozuka is also proud of her alma mater’s history of engagement with Japanese American students, pointing out that in 1942, when U.S. government officials came to take five Japanese American students from campus to an internment camp in Wyoming, La Sierra College President Erwin E. Cossentine pledged to rescue them. He succeeded in his efforts to remove them and about 15 other Pacific Union College and Loma Linda University students from the camps so they could all return to school. (Read more on page 32 of the Fall 2016 issue of La Sierra University Magazine.)

Both personally and professionally, Shinozuka finds the histories of Adventism, Christianity, science, medicine, environmentalism, the U.S. and Japan, race, ethnicity, gender, and culture all deeply interesting. They come together in her teaching, as well as in her forthcoming book, tentatively titled Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950—a project 10 years in the making that will publish with the University of Chicago Press in 2022. “For me it has been quite a journey, kind of like turning back to my roots, to be able to write a book related to this topic,” she says. “Though it has been easier to write about Japanese Americans as they relate to the environment.”

The project is a summation of her current work, flavored by her upbringing, her passion for the environment and humanity’s place in it. In the book, she argues that beginning in the late 19th century a constellation of American responses to Japanese plant, insect, and human immigrants constituted an historical instance of the centrality of biology to racial meanings, all coming together in a complicated and nuanced bias against Japanese American and other Asian American demographics.

The Groundbreaking Begins

In the ‘90s, Shinozuka attended San Gabriel Academy and later enrolled at La Sierra with many of her high school friends, believing it would be better in the long run than attending a secular public school.

“My time at La Sierra included some of my most memorable and happy years because my professors were exposing me to all kinds of ideas I had never heard before. I had great professors who pushed me and shaped me intellectually and who represented and embraced diversity,” Shinozuka recalls.

At the time of her graduation in 1999, Shinozuka was breaking barriers as the first Gender Studies minor at La Sierra. “My Women’s and Gender Studies classes really opened my mind to a different critique of science. It was pretty revolutionary,” she remembers. “I took a religion and gender class with Ginger Hanks-Harwood and Fritz Guy where we talked about gender in the Bible centered on ideas of shalom and love. To this day, I look at the Bible differently.”

She continues, “In terms of ethnic studies, I took my first-ever Asian American history class from the late Clark Davis at La Sierra. I felt so fortunate to have an Asian American class at all, prior to doing Asian American studies at UCLA. I felt very prepared to take on the Asian American graduate studies program where I wrote my thesis on the role of Asian American women in medicine. Classes offered some very sharp critiques on science from a feminist perspective which opened for me the questions on whether or not science was truly objective. Together it gave me a great perspective and opened my eyes to the injustices among many groups.”

Shinozuka later earned her Ph.D. in Modern American History with additional studies in the history of medicine, environmental history, history of science, and Asian American history from the University of Minnesota so that she could speak to a broader audience and merge these concepts with ethnic and racial issues. Her continuing goal is to bring about better understandings leading to reduction in racial issues, discrimination, and equating people with plagues through associating environmental issues with racial groups.

Bridging the Race and Science Gaps

Shinozuka sees clearly how being raised as an Asian American Adventist with the idea of “do justice and love mercy” combines with her pursuits in history, political and medical science, and women’s and gender studies, to give her students a foundational understanding of the injustices toward all groups—and, when exposing systemic racism in certain sectors of society, what to do about it.

“A lot of these concepts culminated in ideas of how Japanese Americans have been perceived in terms of the environment. There have been certain things written about Japanese Americans from historical and more-than-human perspectives,” she laments.

“Japanese Americans have been importing plants since the turn of the 19th and the 20th centuries. For example, take the Japanese cherry trees in Washington D.C. The Japanese government sent them as a gift, but what is not widely known is the first batch in 1910 was burned. It had been deemed infested because of a racialization process that’s not talked about. An entomologist for the USDA at the time said the trees came with all these injurious insects. They attacked Japanese immigrant plants as suspicious with potentially deadly pathogens,” she explains.

Shinozuka says injurious insects became an agricultural and environmental problem resulting in a thinly veiled attack on Japanese immigrants, and their descendants. The result eventually equated the invasive plants, pests, and pathogens with Japanese agricultural workers. By classifying the plants and insects as dangerous, or at the least undesirable, it was easy to make the jump to the people themselves.

“That’s what the book project is about…these little-known stories of how imports may have posed a threat to a newly emerging American empire, especially while acquiring territory, making fortunes, and recruiting exploitable Asian labor.”

She tells of how Hawaii was transformed by white settlers intent on maximizing profits instead of sustaining the naturally diverse and self-sustaining environmental economy. They utilized one or two major crops such as sugar and coffee that eventually took over the islands. Reducing the resident natural diversity resulted in the growth of pests and plant diseases. The same happened in many areas throughout the U.S. mainland, changing the environment and making it more hospitable to injurious insects that were racialized simultaneous to the arrival of Japanese immigrants.

Defeating Ignorance

“The stereotypes of Asians in Southern California as urban horticulturalists who raised gardens and sold their produce were routinely accused of using human waste as fertilizer in an effort to poison people. They were portrayed as a menace to the environment and public health. The response to the perceived menace was a racist and violent one. Media portrayals, including the dehumanizing WWII era-cartoons of Japanese as insects, were circulated in the media leading up to the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

“It’s like the bubonic plague that broke out in turn-of-the-century San Francisco. It was known as the ‘Oriental’ plague. However, the actual problem was international, much like the current coronavirus; but in San Francisco, there was the specific and direct racialization of East Asian immigrants by requiring them to be inoculated and carry a certificate proving they had been vaccinated.”

With this perspective, it’s easy to understand that what’s happening today with the racialization of the coronavirus is nothing new. For example, she points out harmful and misleading terms like “Wuhan” or “China” virus that have been widely used over the last year. Ascribing racial and geopolitical identifiers to a disease—such as “Oriental plague” for the bubonic plague, “Asian” chestnut blight, or even “Oriental” beetles—is a convenient way to use labels that carry racially discriminating undertones.

She finds it troubling, as an environmental historian, to single-handedly blame China for the coronavirus outbreak and questions the science around it because, as she says, it’s not an exact science that accurately traces its origins.

“Why did this virus even emerge on a global scale? Because of the increasingly closer relationship we have with our environment,” she explains. “Moving closer and closer and closer to the environment involves decimating it and annihilating whole species.” This is one reason why, with our global economy, insects and diseases can easily hop a ride on planes or freighters.

Shinozuka sees why it has become easy for pandemics to grow and spread rapidly and widely in an age with so many humans in big cities with huge amounts of interaction. It’s compounded by mass transit, global travel, the elimination of great swaths of forests and rainforests (and their native species), and the efficient shipping of foods, plants, animals, soft and hard goods. These are all viable methods for a virus to travel.

“We have created a fairly narrow target environment for coronavirus and other pathogens in which to thrive. Where else can they go?”

Justice, Mercy, and Eradicating Stereotypes

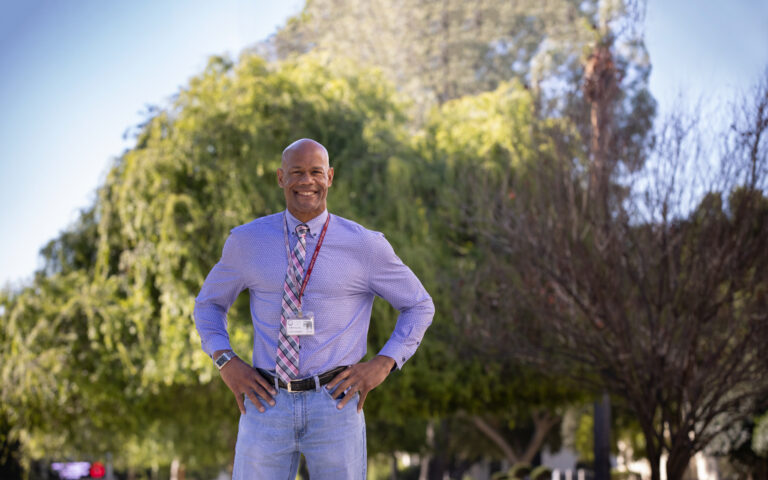

Dr. Shinozuka visiting the Japanese Garden at Huntington Library

So, how can humanity employ the teaching of “do justice and love mercy” in the face of all this racialized environmentalism that is damaging to communities of color in so many racial, social, psychological, economic, and environmental ways?

For Shinozuka, it’s obvious that change must begin in addressing the dangerous stereotypes still held in science and medicine, and public policy which result in health practices that don’t meet the needs of people of color.

A prevalent stereotype she mentions is one that has been viewed for too long as harmless: “that Asian Americans are the ‘model minority,’ that we don’t really face discrimination, that we’re just sort of honorary whites and that we’re extremely successful and wealthy and have no health issues.”

According to Shinozuka, if that thinking prevails it devolves into “if Asians have succeeded, why can’t other minorities?” That, in turn, impacts a public health policy that has not been able to address systemic inequalities of care that people of color receive—or don’t receive.

Ultimately, she explains, “Those who have studied the history of medicine and the health sciences have not studied ethnic and racial minorities. That’s why it is all the more important to reach out to them and build a bridge with other disciplines.”

When it comes to viewing people separately from the environment, Shinozuka is clear: “I don’t,” she says. “That’s why my research takes on a public health, environmental approach. I’m interested in both, and the interrelationship of it all.” And that, she says, got its start for her at La Sierra in the variety of specialized interest classes that later congealed into a bigger, more important picture.

“Historically speaking, it’s been people of color who have been caretakers of the land. Prime examples are not just African Americans, but American Indians and their close relationship to the land, and Latinos and their work in agriculture. It’s a history of communities of color that needs to be reclaimed. We need to have a growing awareness and tell how communities of color are being disproportionately impacted by climate and other environmental changes,” she says. “Very little has been written on people of color and the environment. That is a huge concern. As an academic as well as a Japanese American Adventist, one of the long-term goals of this project and my teaching is to change that.”

And as divisive as the country has become, she sees an even bigger need to trumpet compassion and cooperation that comes from doing justice and loving mercy to bring people together in the fight against the pandemic, racial biases, and interdisciplinary ignorance to help people heal from the societal upheaval that comes as a result.

“This virus doesn’t care what your politics are, what your race is, or whether or not you’re a Christian. What I want for my audience—for the book and in my classes—is to think deeply about the environment and how we are an integral part of it. All this can bring us to ‘do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God’ if we make a change and meet the needs of minorities.”